I was 8 years old.

I had been standing outside of Famous, the pizza house on Main St, for about an hour when my father made me come inside, convincing me that no one was coming. It must have been cold, and I must have been a sad sight to behold, seeing as my birthday is a week before Christmas.

I remember looking up and down the street, wondering where everyone was. Desperately watching the corners and feeling more and more sad. There were tables set up inside with paper hats and streamers, hot pizza on their circular metal trays waiting for someone to come and eat them.

I assume that this was the first time my father had ever thrown a birthday party by himself. I don’t remember a time before this where he was in the lead. He was always there and always loving but never held much responsibility. It had been his job to laugh and hold court with the adults, he and my parent’s friends relaxing in corners or other rooms drinking Heinekens and laughing.

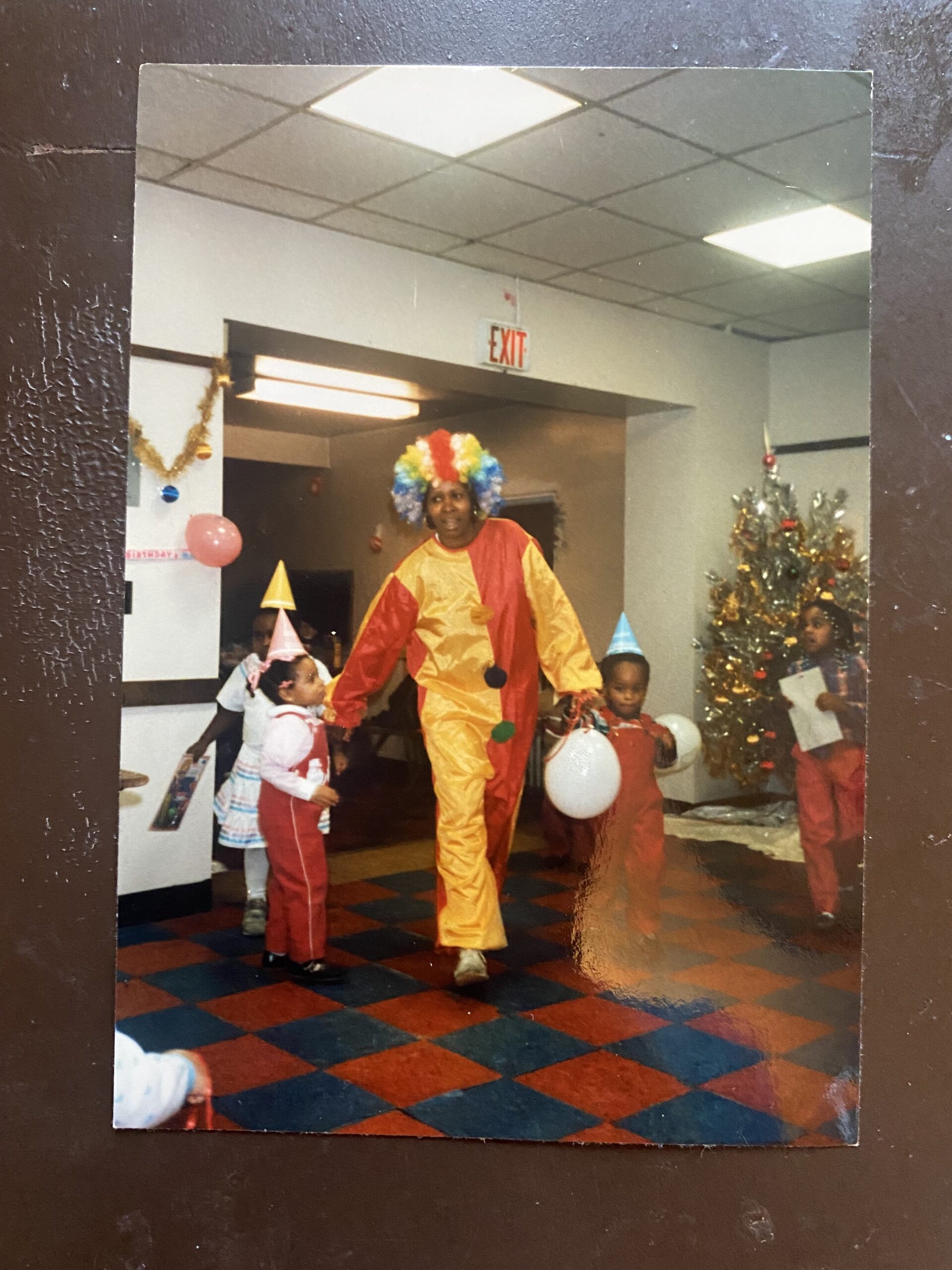

Before this birthday, my mother had held the responsibility of party host. She was the queen of all celebrations: always either dressed up as a clown or conducting easter egg hunts. She served cookies her and my grandmother had read about in Woman’s Day Magazine and served heart shaped brownies. All holidays under her care were a big deal: Halloween, Christmas, even Valentine’s Day.

But I guess this birthday was meant to be remembered for more than celebrations.

I could explore the dynamics that might have contributed to the breakdown of this party: the anger and dysfunction festering between family members, the feelings of loss and heartache that a newly widowed, single father must have been experiencing or perhaps the breakdown of communication and slow decline of financial resources. But none of that matters now. What I remember most about turning 8 years old was that year 8 marked my first memory of loss.

Loss of a parent.

Loss of childhood innocence.

Loss of secure feelings.

A recognition that things would never, ever be the same again.

Standing in front of that empty party marked the beginning of knowing what it felt like to need people, to expect good things and yet to not receive what was needed, not because anyone was at fault but because loss and grief are an inevitable part of life.

Everything in me wanted to curl up into a ball, right there on the sidewalk, and to die. I wanted to throw hot pizza at the walls. I wanted to sit at the table and will someone to show up. I wanted to react in a way that spoke to what I really wanted to do: force people to stay around and love me or die right where I was. And I wanted to feel justified in doing so.

That party was the beginning of my search for security. It was the start of a long journey that taught me that although the emptiness was real, I held responsibility for a continual pursuit of connection. I never wanted to feel, or wanted anyone else to feel, the way I did that day. And although I dove even deeper into depression and regression after this, I always knew that I had to choose something different from how I was reacting at the moment. So instead of standing on that sidewalk indefinitely, I figured that I had no choice but to drag myself inside. To go and figure out how to live a life where I either never felt that way again or learned to thrive, and not just survive, in it. And if I could help someone else to do the same, even better.

That party sucked. Royally. But I am not mad about it anymore. The adult in me recognizes that if I hadn’t been left alone in so many ways, how would I have truly learned to pursue joy amidst a life filled with loss?